The presidency of every country across the world is very essential such that the evolving power and enlarging scope of responsibilities have made the modern presidency a very big job.

The fact that more than anyone else, the President symbolizes the country – its people and its beliefs, the founding fathers of the Ghanaian democracy knowing too well the enormous responsibility this job comes with decided to carve a seat which serves as an insignia to represent the power of political leader known as the presidential seat or seat of state.

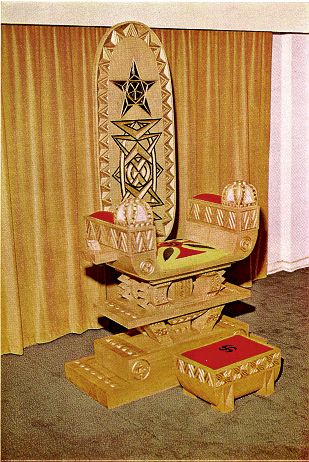

In Ghana, after the oath of office has been taken by the elected president, the Presidential Seat, a carved wooden seat overlaid with gold is handed over to the president to display the rank of his/her office and is used on special occasions.

The presidential seat (Seat of State) is made up of various Ghanaian traditional (adinkra) symbols and some borrowed ideas.

Kofi Antubam, one of the chief ‘state artists’ of the Nkrumah era crafted The Seat of State in the early 1960s (Hess 2001, p. 72).

Antubam also painted a number of murals and carved wood reliefs for public buildings, among them Accra’s Central Library, the Ambassador Hotel and the main assembly hall of the old Parliament House, and he organised state ceremonies and artistic events for the Arts Council of Ghana.

He was part of a remarkable generation of dreamers and nation builders who developed the cultural identity of Ghana.

His works and performances brought together European representational conventions, ‘neo-Ghanaian’ elements such as the Black Star, and motifs borrowed from ‘traditional’ regional and local artistic styles, preferably from Asante, but also other ethnic groups and regions.

Antubam believed, according to Kojo Vieta, ‘that Art must reflect the values and ideas of a society …, should be applied to utility objects… [and be made] a vital part of everyday life’ (2000, pp. 115−6).

In his published views about what the ‘serious modern Ghana artist’ should create, Antubam maintained that the new Ghanaian artistic identity would be ‘neither Eastern’—a reference to the Soviet Union’s tradition or socialist realism—‘nor Western and yet a growth in the presence of both with its roots deeply entrenched in the soil of the indigenous past of Africa’ (1963: 129, 23, quoted in Hess 2001: 73−4). Ghana’s new art needed to be based on ‘the lasting values of a people’s traditions’, but should also take advantage of the ‘better and more progressive implements, skills, and knowledge’ that the history of European art provided (Antubam 1963, pp. 13 & 129).

A look at the Seat of State reveals that its base is modelled after an Asante chiefly stool. Such stools are regarded as central objects of power that connect the chief with the ancestral world and the power of his predecessors. They often represent proverbs that address the relationship between wealth, wisdom and authority, and other constituents of chiefly office. The specific stool ‘quoted’ in Antubam’s Seat of State is the kotoko dwa, a stool that represents one of the central symbols of the Asante nation, the porcupine (kotoko).

The Asante nation, according to a well-known proverb, works like the quills of the porcupine: when one falls, hundreds of others will come to its aid. The porcupine thus stands for solidarity and combativeness.

The artist’s use of the stool simply depicted his intent to link the Ghanaian President’s authority to pre-colonial traditions of state-making and royal power. The bright golden sheen of the Seat of State and the carved stool at its base evoked, indeed, the Golden Stool, the venerated image of Asante statehood which was, as McCaskie put it, ‘construed as being the enabling instrument, the representation, that all at once underpinned, validated and guaranteed the legal exercise of sovereign right. In Asante political philosophy, the Golden Stool … was understood to be symbolic of the highest level at which power might be exercised’ (1983, p. 30).

The seat also invokes not only African pre-colonial emblems of power, but also European aristocratic imagery. The upper part, and the arm rests which are topped with small golden crowns, are designed like a British monarch’s throne.

It is believed that Antubam must have visited Westminster during studies in London and drew some inspiration from the royal throne in the House of Lords where the British Queen sits when she opens a new parliamentary session and addresses the nation.

More generally, as the long-standing parliamentary clerks K. B. Ayensu and S. N. Darkwa put it in their history of the Ghanaian parliament, ‘Ghana adopted the Westminster model of parliamentary democracy’(1999, p. 119), including most aspects of parliamentary procedure.

The English Coronation Chair may have been another of Antubam’s sources of inspiration because it bears a highly significant ‘traditional’ object of power at its base, known as the Stone of Scone.

One may speculate if Kofi Antubam perhaps quite deliberately placed the Asante stool in a position analogous to the one occupied by the Stone of Scone in the English throne, namely as incorporation of an ancient tradition symbolic of the foundation of power as well as a celebration of the victory of the new regime over the old authorities. Given that Nkrumah had to face, and overcome, quite significant resistance from Asante nationalists and prove himself sovereign over the pre-colonial, and later colonially backed, chiefdoms, this interpretation may not be too far-fetched.

The crescent (or the Osramfa) which forms the actual seat symbolizes the influence of feminine disposition and nature on the well-being of the society and State. The egg or oval shape (Okosuasii) which forms the backrest symbolizes perfection in all that is beautiful in the existence of the society.

The zigzag symbol used on the arm-rest and as a border in the oval shaped back-rest counsels the occupants of the seat on the exercise of prudence and diplomacy in all dealings.

The box-like seat has a red cushion bearing a black Nkyinkyin symbol of selfless service. The red colour stands for youthful life and vigour.

The rectangular hand rests represents Mbensu and bears on the sides a frieze of zigzag motif called Ovu-Koforo-Adobe, symbolizing exercise of wisdom or prudence.

This symbol appears on the sides chair as a way of emphasizing importance of the fact that the Head of State must be an embodiment of the qualities of wisdom.

The side-stands of the seat, which have the form of dome, symbolizes God’s grace. The footstool or rest bears on the front of it a Fihankera, the symbol of a perfect house.

Finally, Antubam decorated the Seat of State with one of Ghana’s most prominent ‘neo-traditions’, as one may perhaps call them, namely the Black Star, the Lodestar of African Freedom, which Ghana also displays in her coat of arms, flag and, very visibly, on the Independence Arch.

For Nkrumah and other CPP leaders, the Black Star therefore symbolised hopes not only for the decolonisation of the African continent, but also for a liberating impact of Ghana’s and other African countries’ independence on racial emancipation in America.

REFERENCES

Allman, Jean. 1993. The Quills of the Porcupine: Asante Nationalism in an

Emergent Ghana. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Antubam, Kofi. 1963. Ghana’s Heritage of Culture

Ghana Observed: Essays on the Politics of a West African Republic. Manchester: Manchester University Press. Ayensu, K. B. and S. N. Darkwa. 1999.

The Evolution of Parliament in Ghana. Accra: Sub-Saharan Publishers. Ayensu, K. B. and S. N. Darkwa. 2006.

How our Parliament Functions: An Introduction to the Law, Practice and Procedure of the Parliament of Ghana. Accra: Sub-Saharan Publishers.

Hess, Janet B. 2000. Imagining architecture: the structure of nationalism in Accra, Ghana. Africa Today 47 (2): 35−58.

Hess, Janet B. 2001. Exhibiting Ghana: display, documentary, and ‘national’ art in the Nkrumah era. African Studies Review 44: 59−77.

Kimble, David. 1963. A Political History of Ghana. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

McCaskie, T. C. 1983. Accumulation, wealth and belief in Asante history. I. To the close of the nineteenth century. Africa 53 (1): 23−43.

McCaskie, T. C. 1995. State and Society in Pre-Colonial Asante. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vieta, Kojo T.. 2000. The Flagbearers of Ghana. School Edition I. Accra: ENA Publications.

Wilks, Ivor. 1975. Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wilks, Ivor. 1993. Forests of Gold: Essays on the Akan and the Kingdom of Asante. Athens: Ohio University Press.

August 26, 2016 at 7:30 am

Good work Bro

LikeLike

August 27, 2016 at 10:06 am

Thanks boss

LikeLike

August 26, 2016 at 8:33 am

Good work!

LikeLike

August 27, 2016 at 10:05 am

Thanks dear

LikeLike

August 29, 2016 at 10:12 am

Very informative

LikeLike

August 29, 2016 at 2:56 pm

Thanks

LikeLike

September 28, 2016 at 7:28 pm

Thank you so much boss

LikeLike

May 2, 2019 at 9:21 pm

Thanks to all Solomon Antubam

LikeLike